Whither the Lonely Firefly?

I saw my very first firefly in Los Angeles… Let me explain.

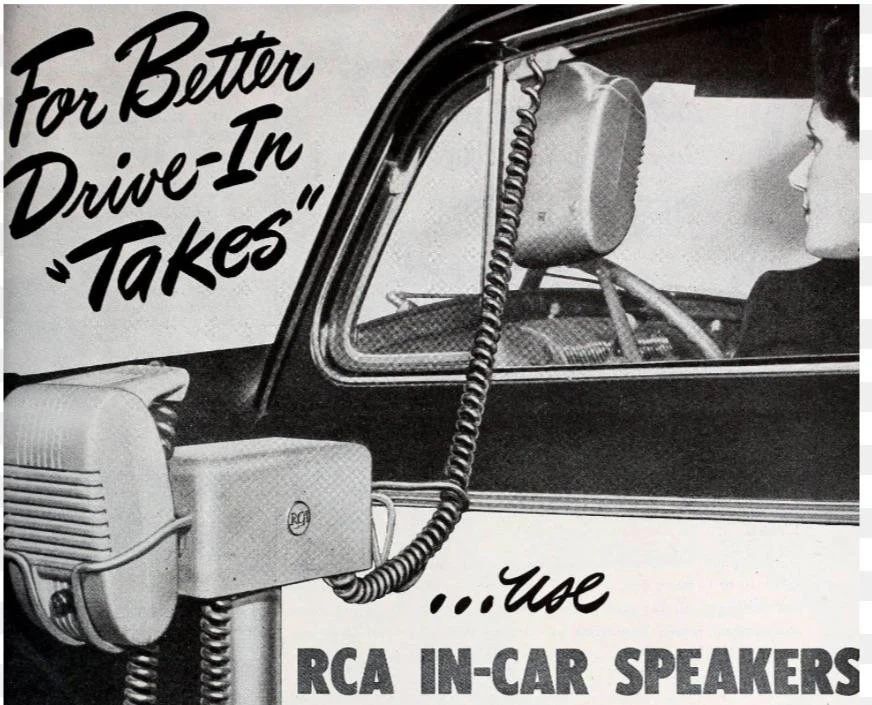

When I was a young boy—perhaps five or six—my parents took my brother and me to Disneyland in Anaheim, California. This was back in the day when a frequent family outing would be to the local drive-in movie where dad would reverse the station wagon up the hump that angled the car towards the huge screen, roll down the window and mount the tinny metal speaker on its edge. We’d crawl into the back of the station wagon, snuggle under some blankets, and watch the movie, generally something from Disney. Point being, I was well familiar with the Disney animated pantheon: Winnie the Pooh, Sleeping Beauty, Snow White, et al.

Disneyland was, thus, an overwhelmingly awesome experience. But what about the fireflies, you ask! I vividly remember lining up for the “Pirates of the Caribbean” ride, stepping into the little boat, and floating gently around the inexplicably serene and enchanting vignettes on the “shore” with their animatronic figures and elaborate sets. One little scene (in my memory at least) featured an old-timer rocking in his chair on a wooden porch while little points of light danced around him.

Somehow, even at that age, I immediately knew that we were in the South and that I was seeing fireflies on a sultry summer evening. I was mesmerized.

(Then, of course, the boat plunged down a waterfall into some deranged netherworld of “Yo ho, Yo ho, a pirate’s life for me!” (thirty years pre-Johnny Depp) right on the edge of exhilarating terror for me and my brother. Despite that sensory overload, I have never forgotten those dancing fireflies and the umami-sense of peace they gave. But I digress.)

Winter may seem a strange time to be writing about fireflies. Again, let me explain.

I am fortunate to live near a large open park populated with huge deciduous trees: oaks, maples, and Sugargums (Liquidambar styraciflua). Sugargums notoriously drop thousands of hard, round, spiky seedpods that we call “gumballs” but which are more like little landmines that make walking through them in sandals or flipflops (let alone bare feet) a “do-it-once-in-your-life” affair.

I frequently head through the park on my morning walk. Last week, despite the fact that, it being winter, there was no grass under the thick tree canopy to mow (said canopy and the shade it throws also being responsible for there being very little grass there at any time of year), the city maintenance crew was out busy mowing in tractor-sized seated mowers. Plumes of shredded leaf litter and dust spewed from the mowers’ discharge chutes before settling right back to earth. It wasn’t clear to me what purpose the “habitat decapitation/mass insecticide” (the actual scientific terms) served other than, perhaps, to encourage the leaf litter to decompose?

I found myself thinking back to my boyhood visit to Disneyland, this time to the “Adventure Thru [sic] Inner Space” ride sponsored by (ironically for the purposes of this essay) Monsanto. In case you missed this ride before it closed in 1985 to be replaced—fittingly—by “Star Tours,” it went like this: you got onto an automobile that traveled through the “Monsanto Mighty Telescope” to explore snowflakes at molecular and atomic scales. Confusingly, the premise seemed to be that rather than magnifying the world around you as you might expect from a microscope, it was you yourself who shrank tinier and tinier until you could pass through an atom with electrons whirling around you. (Needless to say, a day spent at Disneyland constituted hyper-sensory overload to an impressionable five-year-old!)

Although I am not generally a visual or kinesthetic thinker (I am close to a 5 on the aphantasia scale), upon seeing/hearing/smelling the lawn mowers in the park last week, I felt myself shrinking to larval size and viscerally experiencing the violent destruction of the entire known universe as the machines roared over me. To be clear, I am not suggesting that larvae and insects and worms have subjective conscious experience. (Nor am I blaming the city workers who were just doing their assigned job.) Nevertheless, as mini-me—and just for a moment—I felt terror and grief as a storm more powerful than the worst earthquake or tornado or typhoon swept up me and my family and my home and consigned us all to oblivion.

As I returned to my—thankfully intact—home, actually shaken, I could not help but noticing the piles of bagged leaves lining our streets and the incessant whine of the weed-eaters and mowers and leaf blowers of the ubiquitous mow-blow-and-go operators keeping the neighborhood and its lawns neat and tidy.

Let me be serious for a moment and return to the humble firefly. Globally, scientists estimate that a few thousand insect species are bioluminescent, with beetles making up the vast majority. Within beetles, fireflies and glow‑worms (family Lampyridae) alone contribute roughly 2,200–2,400 described species, all of which produce light in at least one life stage, and additional luminous lineages—including click beetles, railroad worms, and related groups—likely bring the total number of glowing beetle species to well over 3,000.

The fireflies in my neighborhood, in the Appalachians of Virginia and West Virginia where I hike, and those modeled by those clever Disney Imagineers are Photinus pyralis, commonly known as “Big Dippers.” Big Dippers are hardy and widely distributed. They are one of the most widespread fireflies in North America, occurring throughout much of the United States east of the Rockies and into southern Canada, from the Gulf Coast up through the Midwest and Northeast. They thrive in temperate climates wherever summers are warm enough and soils retain some moisture, and are comfortable from sea level up through typical Appalachian and upland elevations (well into the sub‑4000‑foot band and beyond where conditions are suitable).

Crucially, Big Dipper larvae require cool, damp ground with organic cover—leaf litter, thatch, and loose soil in meadows, lawns, woodland edges, and along streams or low wet spots… I’m sure you can see where I’m heading with this.

[To be continued…]