The Role of Ethics in the Design and Regulation of Autonomous Vehicles

Ten years ago, I was in my fourth and final year of undergrad at Stanford University, majoring in the wildly interdisciplinary Science, Technology, and Society. The prior spring, I’d taken a class with the director of the STS program. After reading my writing for her class, she recommended that I join the department’s honors program and spend my senior year developing and writing a thesis (in addition to my regular classes, of course).

So I did.

Also that prior spring, I had taken a class called “Ethical Issues in Engineering,” and did my final project on the ethics of autonomous vehicles. I decided to expand that project into my thesis, with the professor from that class as my advisor.

The body of the resulting thesis was about 70 pages long (with an additional 20+ pages of references and appendices) and consisted of seven chapters: Introduction, Historical Context, Current Technology and Legislation, Literature Review, Research Design and Methodology, Data Analysis and Discussion, and finally, Conclusions.

Although chapters 1-4 contained important background information to set the stage, the bulk of my work was the research and data analysis I conducted. I designed a 40-question survey, got my research plan approved by the Institutional Review Board (which I had to do since I was doing research with human subjects), and sent it out into the world. I was hoping for maybe a couple hundred responses.

I got almost 4,000.

The resulting data set was far larger than I had anticipated, and I quickly realized there was no feasible way to address all of it in a single undergraduate thesis. I would have to pick a subset of the survey questions to make my primary focus.

In addition to general questions about autonomous vehicles and their potential ethical challenges, I presented my respondents with a variant of the famous Trolley Problem thought experiment called the Tunnel Problem. (I can’t take credit for inventing the Tunnel Problem; I encountered it as part of my literature review research and adapted it for my own purposes.)

The gist of the Tunnel Problem is that an autonomous vehicle gets into an unavoidable crash situation in which either the person in the vehicle or a person in the road in front of it will die. I created four variants of this “ethical no-win” scenario for my survey.

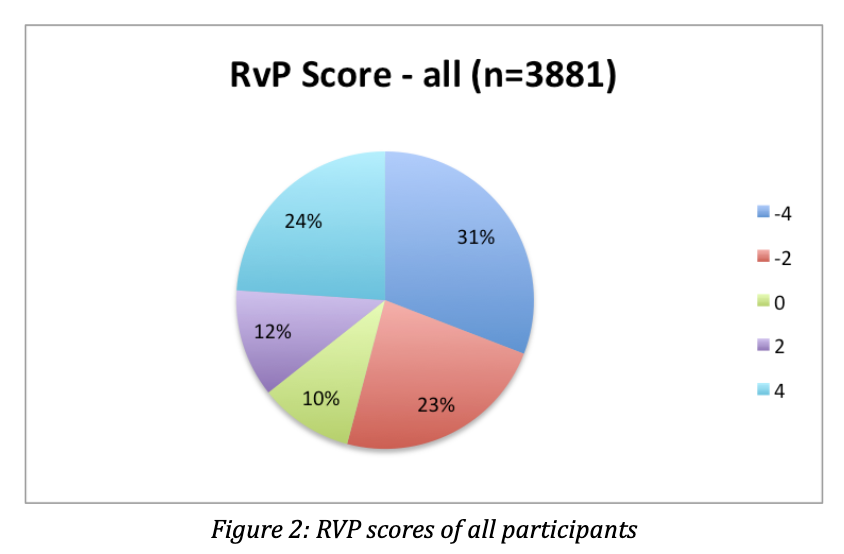

What I ended up focusing on was subjects’ “moral consistency” across the four scenarios, giving each respondent a “Road-vs-Passenger,” or RVP, score from -4 to 4. The ends of the scoring scale indicated that the participant had made the same choice in all four Tunnel Problem variants, either always sacrificing the person in the road or always sacrificing the person in the car.

These low- and high-end scores were the most common, demonstrating a high degree of consistency. The next most common score was -2, meaning that in three of the four scenarios the person in the road was sacrificed over the person in the car.

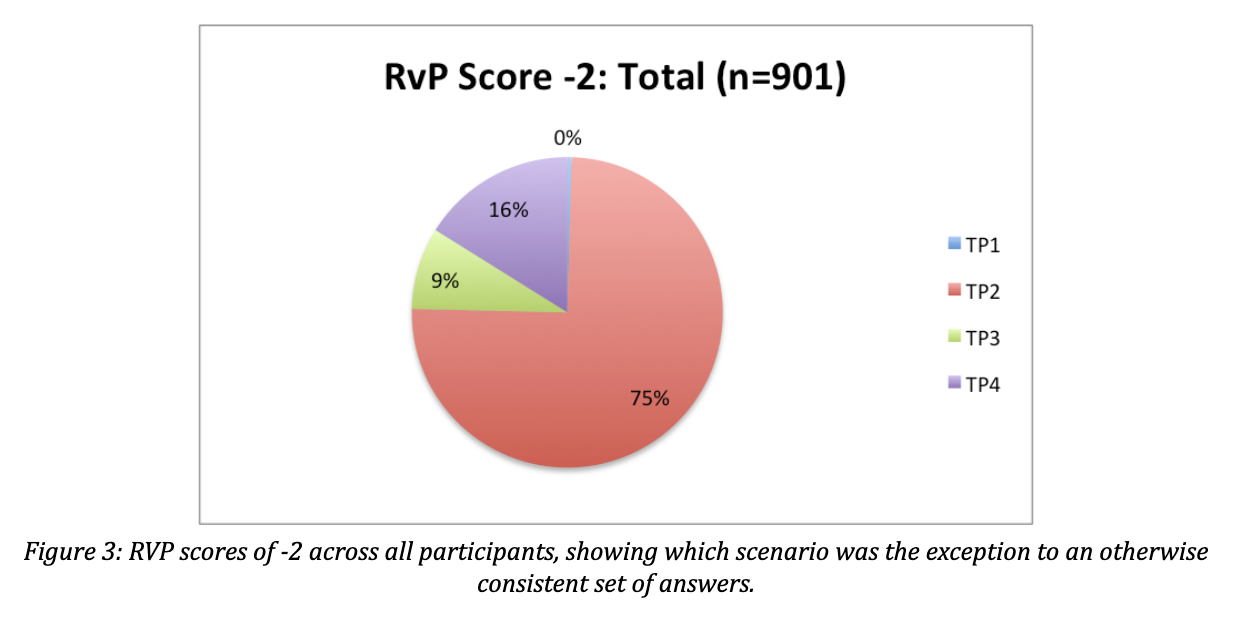

This discovery led to an interesting hypothesis. In three of the four scenarios, there was one person in the vehicle and one in the road, but in the fourth scenario there were three people in the road whose lives were at stake. My guess was that it would be this fourth scenario in which participants chose to sacrifice the occupant of the vehicle, a “utilitarian override” to otherwise consistent moral reasoning.

I was right.

75% of the -2 scores deviated for the scenario in which utilitarian ideals were at stake, rather than a 1:1 ratio of lives at risk.

Other questions in the survey revealed that, in general, people would prefer that autonomous vehicles have some conception of who (or what) is “at fault” in an ethically challenging scenario, and to prioritize the safety of those perceived to be “not at fault.” The RVP scores of -2, however, indicate that in some cases this way of thinking may yield in the face of utilitarianism.

There’s no way I could summarize my entire thesis in one newsletter post, but it was a fascinating project (if overwhelming at times).

Ten years ago, the autonomous vehicle landscape was very different than it is today. Finding other sources discussing ethics was somewhat challenging (although my bibliography turned out to be quite extensive in the end). Autonomous vehicle ethics was very much still an emerging area of research and discussion.

Although I haven’t worked directly with autonomous vehicles in several years, I still try to pay attention to the happenings of the industry and the debates surrounding it. As autonomous vehicles become increasingly widespread, figuring out what ethical behavior looks like for them and how to implement that becomes increasingly important. I’ve loved seeing awareness of this area grow and spread, both within the industry and beyond it, and I’m excited to keep watching what happens next.

In my current graduate program—Philosophy of AI at the University of York in England—we’ve recently been talking about AI ethics. This is a hugely important area that reaches well beyond the sphere of autonomous vehicles. From sex robots to ChatGPT, AI is growing and spreading like never before, and we need people focusing on the ethical impacts of these developing technologies.

The AI industry is huge, and the wake it leaves will be—already is, in fact—huge as well. How can we make sure that wake is left clean?

On the off chance anyone feels like a deep dive into the state of autonomous vehicle ethics in 2015-2016 (or if you were one of my survey respondents—I know you’re out there!—and want to revisit the project), my thesis is available here. (And you thought my dad’s full speech on “When Words Get in the Way” was long! Fasten your seatbelts and settle in.) And if you’re curious about my later work with autonomous systems at Udacity, you can find some of it here.

I was awarded a Firestone Medal for Excellence in Undergraduate Research for my thesis, so I’d say it came out pretty well!